A cinema screen is a portal. It pulls you in, silences the outside world, and makes you forget where you are. That magic, the feeling of stepping into another world, is disappearing across Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Egypt. The seats are still there. The popcorn still pops. But fewer people are showing up.

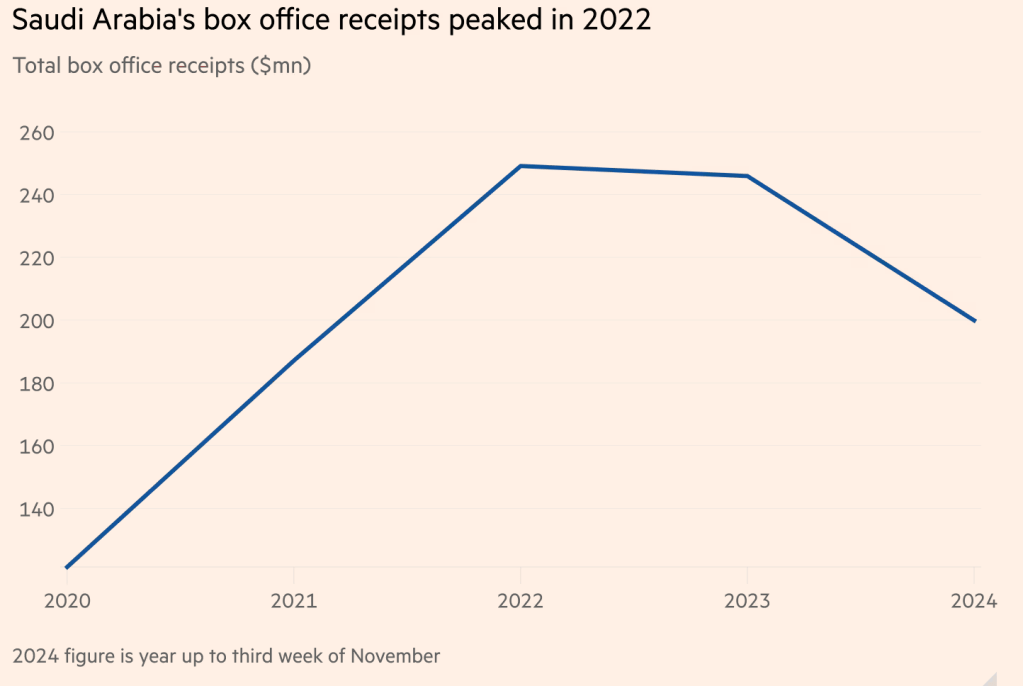

This was supposed to be a golden age for Middle Eastern cinemas. Saudi Arabia reopened theatres in 2018 after a 35-year ban. AMC predicted a billion-dollar industry. Box office numbers climbed fast, peaking at $249 million in 2022. But by late 2023, revenue had dropped to $200 million, and it is set to decline again in 2024. The UAE and Egypt, once the region’s strongest markets, are also struggling. As I just read on the Financial Times.

People still love movies. They are just watching them somewhere else.

The Three Cuts That Are Killing Cinemas

1. A Self-Inflicted Dead Zone

Every year – in example is this year – from February to April, cinemas across Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Egypt slow down. Theatres delay major releases for Ramadan, which means there is little to watch for months. That might have made sense decades ago when entertainment options were limited, but today, audiences move fast. A dry spell pushes them toward streaming, and once they leave, many do not come back.

Other markets handle this differently. Turkey and Indonesia schedule major films before and after religious holidays, keeping audiences engaged. The Middle East does not. Instead, cinemas expect people to wait. They don’t.

2. Movies Are Getting Censored to Death

A good story needs a beginning, a middle, and an end. Saudi Arabia’s film censorship often removes one or more of those. It is not just about trimming scenes. Entire subplots disappear, characters are rewritten, and in some cases, movies never make it to screens at all.

Films with LGBTQIA characters are frequently banned. Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse, Eternals, and Barbie were either heavily edited or pulled entirely. Instead of fighting for uncut versions, distributors censor films even before submitting them. This happens in the whole region, with Kuwait driving the “moral” trend.

Audiences are not naïve. They know they are paying full price for a film that has been cut apart. Why bother?

3. The 30-Day Problem

Even if cinemas somehow solved the first two problems, they still face one impossible battle. Hollywood movies hit streaming services within a month of their release. That is the legal route. The illegal one? Even faster.

A two-year-old could find a full HD version of a new movie online in minutes. Why drive to a theatre, pay for a ticket, and watch an edited version when the full one is available at home?

The UAE has some of the most advanced cinemas in the world. Egypt has a deep-rooted film culture. Saudi Arabia poured billions into making itself a regional film hub. None of that matters if audiences stop coming.

Monopolies, Distribution Power Plays & The Festival Gap

Theatres are losing audiences, but distributors are also to blame. Instead of helping cinemas thrive, they have turned into gatekeepers, controlling what gets shown and where.

Majid Al Futtaim, the region’s most dominant distributor, has been swallowing licenses left and right:

- Took Warner Bros. Entertainment Middle East from Shooting Stars

- Took Universal Studios Hollywood from Four Stars

- The only major studios left outside its grip are Sony (with Empire), Disney (with Italia Film International) and Paramount (with Four Stars)

What is left for independent cinemas? Peanuts.

This monopoly hurts variety. Majid Al Futtaim prioritises Bollywood blockbusters over Hollywood, Arabic and independent and foreign films (because it makes more money?), making it even harder for smaller distributors to compete. Not only that, but controls release dates of some over the other and does self-censorship sometimes to avoid having to go through approval & censorship processes.

Others have found ways around this mess. Front Row Filmed Entertainment, one of the region’s most respected distributors, skips cinemas entirely. Instead of screening heavily censored films, it goes straight to VOD, where uncut versions can be shown legally. It is a rational business move, but it also means fewer diverse films ever make it to the big screen.

What About Film Festivals?

Festivals could be an alternative space for diverse storytelling, but the region has too few of them. Outside of Egypt’s Cairo International Film Festival and El Gouna Film Festival, the only major platforms are:

- The Red Sea InternationalFilm Festival (Saudi Arabia)

- Amman International Film Festival (Jordan)

That is it.

These events provide limited windows for alternative films, but they are not enough to replace a functioning cinema industry. Festivals should be launching films into wider releases. Instead, they have become isolated moments that come and go without fixing the larger problem.

Censorship Rooted in Moral Codes and Public Decency Laws

The strict censorship in Middle Eastern cinemas is deeply rooted in the region’s moral codes and public decency laws. These regulations are designed to uphold cultural and religious values, often leading to the removal of content deemed inappropriate.

- Saudi Arabia: The country’s censorship policies are influenced by tribal and religious factors, aiming to prevent the depiction of content that contradicts Islamic principles. This includes the prohibition of scenes involving nudity, sexual content, or blasphemy. For instance, public cinemas were banned from 1983 until 2017 to adhere to these moral standards.

- United Arab Emirates: Historically, the UAE censored films to align with its cultural values, removing scenes depicting nudity, homosexuality, or other content considered offensive. However, in a move towards modernization, the UAE announced in December 2021 that it would end censorship of cinematic releases, introducing a new 21+ age rating to allow international versions of films to be screened without cuts.

- Egypt: Under the leadership of President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, Egyptian artists have faced increased censorship, with authorities exerting control over artistic expression to maintain public morality. This has led to a climate where filmmakers must navigate complex regulations to avoid government backlash.

These censorship practices are not merely about controlling content but are deeply intertwined with the desire to preserve societal norms and religious values. While intended to protect cultural integrity, such stringent regulations often stifle creativity and limit the diversity of content available to audiences.

Can Middle Eastern Cinemas Be Saved?

Fixing this is not complicated. It just requires a change in mindset.

1. Fix the Release Calendar

- Stop pushing everything to summer and winter.

- Fill the gaps before and after Ramadan with strong releases.

- Treat the region as one market instead of staggering premieres.

2. Ease Censorship

- Keep a rating system that lets people choose instead of cutting films apart.

- Stop banning films over single scenes.

- Give audiences the full story they paid for.

3. Break the Distribution Monopoly

- Open licensing to multiple distributors, preventing a single company from controlling the entire market.

- Support independent cinemas with access to more diverse films.

- Encourage regional filmmakers to find ways around the system, like what Front Row is doing.

4. Make Cinemas Matter Again

- Offer something streaming does not. Early releases, special screenings, interactive events.

- Change pricing models to match audience expectations.

- Invest in local films that people actually want to see.

The Final Scene

A cinema should be an escape, not an exercise in patience. Right now, people across the Middle East are finding that escape elsewhere.

Once audiences leave, getting them back is far harder than keeping them in the first place. Theatres have a choice: adapt or fade into the background, another screen switched off in a world already filled with too many distractions.

Leave a comment